100th Anniversary of the Balfour Declaration

Tom’s Perspectives

Dr. Thomas Ice

It was not worth winning the Holy Land only to “hew it in pieces before the Lord. Palestine, if recaptured, must be one and indivisible to renew its greatness as a living entity.”[1]

—British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George

On November 2, 1917 the British government issued their now famous Balfour Declaration, which was a statement of British foreign policy at the time when issued. This month, November 2016 begins a year-long commemoration of the Balfour Declaration, which is generally viewed as the first serious step leading to the rebirth of the modern state of Israel in 1948. Of course, the Arabs see the founding of modern Israel as a great disaster and the Palestinian Authority is responding by “preparing a lawsuit against eh British government over the 1917 document that paved the way for the creation of the State of Israel.”[2]

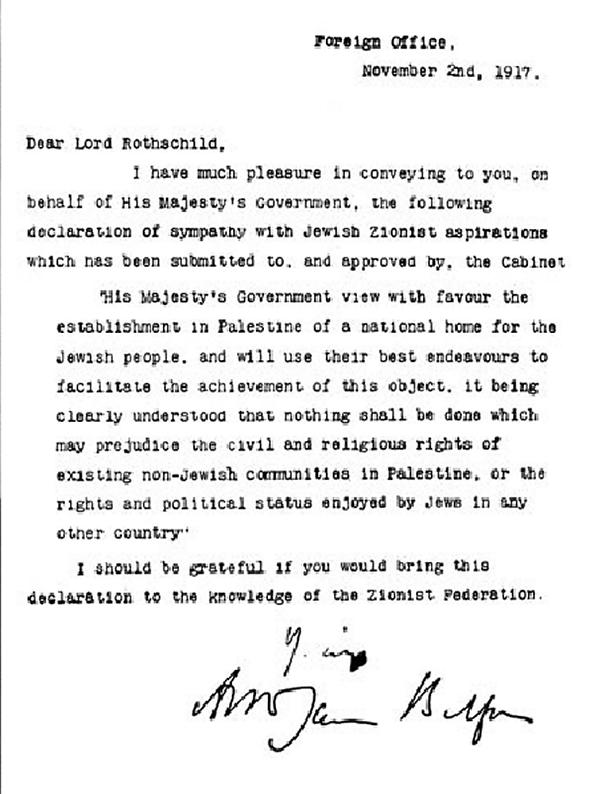

About one hundred years ago, the sun never set on the British Empire when Great Britain issued the Balfour Declaration. David Lloyd George had ascended to Prime Minister on December 6, 1916 and appointed a former Prime Minister Alfred Balfour foreign secretary who handled foreign affairs. The idea for issuing the Balfour Declaration was clearly Lloyd George’s idea but Lord Balfour was in total agreement with him on the matter. Here is a copy of the brief Declaration.

Balfour's Declaration was addressed to Walter Rothschild, who was viewed as the titular head of the British Jewish community in his day.[3] Balfour's Declaration was adopted by Lloyd George’s War Cabinet[4] after three presentations of evolving versions. George and Balfour sought and obtained American support before issuing the Declaration. “President Wilson, decisively influenced by Justice Brandeis via Colonel House, had telegraphed finally an unambiguous message of support for Zionism.”[5] Had Lloyd George not had Wilson’s full support, it is doubtful the British would have put forward the Declaration. The Balfour Declaration was co-authored by Lord Balfour and Andrew Bonar Law, both men were from Scotland and greatly influenced by their biblical upbringings. Looking back, Balfour’s Declaration has rightly been viewed as a major breakthrough launching the process resulting in the foundation of the modern state of Israel. However, in 1917 it was simply an important statement concerning official British foreign policy. It was destined to become much more than that.

The War Cabinet

It is important to take note of who composed the British war cabinet during the Great War in 1917 that approved the Balfour Declaration. The cabinet was primarily made up of committed Zionists. “The one member who was firmly anti-Zionist was also the only Jewish cabinet member: Edwin Samuel Montagu.”[6] “Aside from Montagu, only one other member of the cabinet had been raised in England, and he was also the sole English-born Anglican in the war cabinet: Lord Curzon. . . . These two were the only English members of the war cabinet, and they were the two who were most opposed to Balfour’s proposal.”[7] Eventually Montagu was called to India and was not at the meeting that voted approval on October 31, 1917. The rest of the war cabinet was non-English.

Prime minister Lloyd George was from Wales and adopted into a Baptist minister’s home. Lord Balfour was Scottish, along with three others: Arthur Henderson, George Barnes, and Andrew Bonar Law. Edward Carson was an Irish Protestant. Jan Christian Smuts was from Cape Town, South Africa, as was German-born Alfred Milner.[8]

I don’t know if Lloyd George thought through the religious make-up of the war cabinet or it just worked out that way in the providence of God but it would have been very difficult to have put together a more evangelical group of men who were influenced by the Bible at the highest level of British government in those days than the ones who made up that group. Donald Lewis describes them as follows:

Seven of the nine Gentile members had been raised in evangelical homes or personally embraced evangelicalism. More specifically, six of these seven had been raised in evangelical Calvinist homes: Balfour—Church of Scotland (Presbyterian); Lloyd George—Baptist; Lord Curzon—evangelical Anglican; Andrew Bonar Law—(Presbyterian) Free Church of Scotland; Jan Smuts—Dutch Calvinist; Edward Carson—Irish Presbyterian. Three of them were sons of the manse (Curzon, Bonar Law, and effectively, Balfour). One was a Scottish Methodist—Arthur Henderson. Little is known of the religious backgrounds of Alfred Milner and George Barnes. But clearly the influence of Calvinist forms of evangelical Protestantism dominated the family backgrounds of the majority of the cabinet members.[9]

God certainly had his team in place when it came time to issue the Balfour Declaration. “Dominated by non-English members and by men with Calvinist evangelical upbringings,” notes Lewis, “they did not reflect the British national makeup in either ethnicity or religion.”[10]

Some may wonder about so many with a Calvinist upbringing leading to support for a modern state of Israel. In Great Britain in the 1600s when Puritan Calvinists dominate the island-state, they were almost all very pro-Israel and as restorationists looked forward to the Jews returning their their homeland in the last days. This was still a strong belief among evangelical Calvinists in the late 1800s and 1900s. It tends not to be a view held by most Calvinists in our own day.

The Palestinian Campaign

General Edmund Allenby conquered Jerusalem, and thus the region known as Palestine, on December 9, 1917, a little over a month after the issuance of the Balfour Declaration. The British were bogged down in the Middle East in their offensive against the Ottoman Turks. Lloyd George quietly moved his best general from the Western Front in Europe to take charge of the Palestine Campaign and Allenby did not disappoint. Lloyd George also ordered an increase in the number of British troops to Palestine to make sure the British would capture Jerusalem before the French or the Germans. These moves were done quietly because the “capture of Jerusalem was seen as desirable and ‘as a Christmas present for the British nation,’”[11] according to Lloyd George. In order to accomplish the capture of Palestine, Allenby “received extra aeroplanes, battalions and battleships, and also 10,000 cans of asphyxiating gas to knock out the Turks.”[12]

Lloyd George had been a loyal Zionist for the last two decades before becoming Prime Minister in the middle of the war. It was clear that “he was brought up on the Bible. Repeatedly he remarked that the Biblical place names were better known to him than were those of the battles and the disputed frontiers that figured in the European war.”[13] Lloyd George strongly wanted Britain to control what they called Palestine in those days, so they could help to reconstitute the nation of Israel. This was clearly his motive for opposing his entire general staff, who wanted all resources concentrated on the Western Front, while Lloyd George wanted to include a vigorous effort in the Middle East.[14] There is no doubt his biblical convictions were the primary motive for pressing the Palestine Campaign so vigorously.

Lloyd George was not, like Asquith or the other members of the Cabinet, educated at a public school on Greek and Latin classics; he was brought up on the Bible . . . Unlike his colleagues, he was aware that there were age-old tendencies in British Evangelical and Nonconformist thought that favored the return of the Jews to Zion, and a line of Christian Zionists which stretched back to the Puritans.[15]

There were soldiers from across the British Empire that fought in the Palestine Campaign. Countries where Christianity was the main religious orientation (England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand); have many accounts from the diaries of the soldiers expressing their excitement about being in the Holy Land, which they had read so much about in their Bibles. Many of the troops believed they were part of fulfilling Bible Prophecy or on the verge of those events. General Allenby, who was a devout, Bible reading Anglican himself,[16] asked the men who were Christians not to express their views so as not to cause conflicts in the ranks. Many of the troops fighting with and for the British Empire were from Muslim and Hindu cultures. “On 11 December 1917 General Sir Edmund Allenby and his officers entered the Holy City of Jerusalem at the Jaffa Gate, on foot.”[17] “Directions were given to Allenby to dismount his horse before arriving at the Jaffa Gate and humbly walk through on foot, . . . The War Cabinet wanted a simple, un-militaristic entrance, completely different from the Kaiser’s theatrical parade nineteen years earlier when, with much pomp, he had ridden through the Jaffa Gate on a horse.”[18]

Conclusion

As Christian Zionists like myself reflect upon the sovereign acts of God in history that lead to the reestablishment of modern Israel, it is crazy to think Arabs can somehow change anything by bringing a lawsuit because they did not like what took place in history. We all know you cannot change history, but there is something in the Muslim psyche that leads them to want to change things, as if they did not happen, that did not fall the way they believe they should have. We see this in the Muslim-lead, recent vote in the United Nations UNESCO committee to only use the Arab name for the Temple Mount and to outlaw in official UN business the recognition that Israel and Jesus had anything to do with that site. It should be an interesting year as we commemorate the centennial of the Balfour Declaration. Marantha!

ENDNOTES

[1] David Lloyd George, Memoirs of the Peace Conference (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1939), Vol. 2, pp. 721–22. Cited in David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1989), p. 268.

[2] Times of Israel staff, “Palestinians to launch year-long campaign against ‘crime’ of Balfour Declaration,” The Times of Israel, October 24, 2016, http://www.timesofisrael.com/palestinians-to-launch-year-long- campaign-against-crime-of-balfour-declaration/.

[3] Jonathan Schneer, The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict (New York: Random House, 2010), p. xxi.

[4] During wartime parliamentary governments often select an inner circle of nine to twelve representatives to pass legislation because the normal parliamentary process would be too slow and cumbersome to handle wartime decision making.

[5] Schneer, The Balfour Declaration, p. 341.

[6] Donald M. Lewis, The Origins of Christian Zionism: Lord Shaftsbury and Evangelical Support for a Jewish Homeland (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2010), pp. 332–33.

[7] Lewis, Origins of Christian Zionism, p. 333.

[8] Lewis, Origins of Christian Zionism, p. 333.

[9] Lewis, Origins of Christian Zionism, p. 333.

[10] Lewis, Origins of Christian Zionism, p. 333.

[11] Jill Hamilton, God, Guns and Israel: Britain, The First World War and the Jews in the Holy City (London: Sutton Publishing, 2004), p. 125.

[12] Hamilton, God, Guns and Israel, p. 125.

[13] Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace, pp. 267–68.

[14] Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace, p. 264.

[15] Robert Lloyd George, David & Winston. How a Friendship Changed History (London: John Murray, 2005), p. 176. Cited in David W. Schmidt, Partners Together in this Great Enterprise: The Role of Christian Zionism in the Foreign Policies of Britain and America in the Twentieth Century (Xulon Press, 2011), p. 70.

[16] Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs under the British Mandate (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2000), p. 22.

[17] Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace, p. 312.

[18] Hamilton, God, Guns and Israel, p. 153.